(Read the first part of this blog here.)

Returning to Paris from London in 1872, Paul Durand-Ruel was fired up with enthusiasm for Impressionist paintings, and sought out as many as he could. As well as Monet and Pissarro, he bought work by Degas and Sisley, purchasing in bulk.

Returning to Paris from London in 1872, Paul Durand-Ruel was fired up with enthusiasm for Impressionist paintings, and sought out as many as he could. As well as Monet and Pissarro, he bought work by Degas and Sisley, purchasing in bulk.

As their dealer, Durand-Ruel looked after his artists carefully, making sure that they had the freedom to produce the work without worrying about practicalities. To this end, he paid them monthly salaries against future work, settled bills, and generally provided moral as well as financial support. He also gave them the security of his backing, with the promise of growing profiles, access to clients and exhibition opportunities.

Overall, Durand-Ruel was a risk-taking trend-setter, creating the new taste in art in society by creating desire and demand, and then supplying that demand.

Take a look at Monet's Railroad Bridge, Argenteuil.

Claude Monet, Railroad bridge, Argenteuil (Oil on canvas, 1873, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Now, when I was studying Fine Art, we learnt how the Impressionists painted not only in a new style - quick, loose, expressive brushwork painted en plein air, thanks to the invention of portable, collapsable tin tubes of oil paint - but they used new subject matter, namely the modern world around them.

Monet's painting has a luminous quality to it - it's full of light - but it is also full of drama, as the modern industrial world of the railway plunges across the tranquil river. Just the sort of subject matter that an Impressionist painter looking at the world around him would paint.

Monet's painting has a luminous quality to it - it's full of light - but it is also full of drama, as the modern industrial world of the railway plunges across the tranquil river. Just the sort of subject matter that an Impressionist painter looking at the world around him would paint.

However, if you bear in mind that behind the painter is a dealer, who has a middle class client base lined up to look at your paintings, you are going to obviously have one eye focussed on what appeals to your audience. So it is very striking when you look round the exhibition that not only are all the paintings of a certain size (a size which a painter can carry with him out into a field, but also conveniently fits very handily into the decor of a Parisien sitting room) but also that Monet has been savvy enough to paint a subject with maximum appeal to his customers.

Argenteuil was 15 minutes from Paris by train, and was a popular weekend destination where wealthy Parisiens would hire small boats exactly like the one in the painting. So it's a scene which speaks of the new middle-class leisure activities, and the new ways to travel. This is a scene which appeals to people who are, quite literally 'going places'. It's a highly aspirational piece, all about money and if you put this on your wall, then you're telling everyone that you've arrived.

So the question is - how much were the decisions about subject matter, style, size and presentation dictated by the fact that the Impressionists were working hand in glove with Durand-Ruel? Durand-Ruel manipulated the market to accept the radical new style of painting, but then to what extent did that market subsequently dictate what product the painters produced?

The First Impressionist Exhibition took place in 1874, a landmark year in Fine Art History. It was a year which could easily have bankrupted Durand-Ruel, and consequently the Impressionists, due to a banking crisis and a glut of unsold work.

However, in 1876 they tried again, with Durand-Ruel giving backing, premises and expertise to launch the cunningly named Second Impressionist Exhibition. 250 works went on display, to a lukewarm response.

Paintings included Renoir's sickly sweet "Study: Torso, Sunlight Effect"...

Paintings included Renoir's sickly sweet "Study: Torso, Sunlight Effect"...

Pierre-August Renoir, Study: Torso, sunlight Effect (Oil on canvas, 1875, Musee d'Orsay)

...and Monet's Springtime, showing a middle-class lady relaxing in her finery, but looking more like one of those toilet-roll hiding crinoline dollies on her tea break.

Claude Monet, Springtime (Oil on canvas, 1872, Walters Art Museum, Maryland)

But then...BLAM!!

Edgar Degas, Peasant Girls Bathing in the Sea at Dusk, 1869 (Private Collection, Ireland)

Seeing this across the room at the exhibition, I thought I had just laid eyes on the most stunning painting I had ever seen, and couldn't take my eyes off it. It was unlike anything else in the room.

I stood in front of it for a very very long time.

Lots of people came up and peered at it.

"Is this guy lazy or what?" snapped an American lady.

"Terrible!" declared an elderly woman frostily, rattling her pearls in agitation.

It would seem that Impressionism still has the power to disgust and dismay.

The painting looks very unfinished, the paint thin, the paintwork broad, scratchy or non-existent. But this gives it an energy, a vibrancy, a sense that the moment it captures is so brief - a brevity of movement, of youthfulness, of the sun going down - that it is like a snapshot. This photographic sense is particularly apt for Degas of course, for this is one of his (one I have never seen before, as it is from a Private Collection). Degas made full use of the new medium of photography, by using photographs he took himself as reference material, both as a means to capture difficult poses for his nude studies, and of reinvigorating traditional compositional norms.

Here, the figures combine incredibly minimal information - flat, brown forms painted broadly in thin paint - with heart-breakingly delicate detail, such as the head of the girl on the left hand side, her mouth open, caught in a laugh of delight. The lines used to describe her face and the outline of her body (and of the body of the central figure) are so assured, so confident and so in charge of what they are saying, that It's very, very beautiful. They give weight and direction and structure and volume. I just wanted to stand and cheer. Degas, I see what you did there. And I like it. I understand.

Whilst the two left hand figures have a gorgeous fluidity of line, the right hand one is barely suggested - so much turps is used that the line down the back of her right thigh breaks up. Although their heads are beautifully, expressively realised, their hands, which link the figures together, aren't actually there at all, when you look closely. And on the right at the top are a jumble of strange, out-of proportion, difficult to read figures who appear to have been collaged in from a whole load of different reference material.

The effect of the whole is a strange sense of exhilaration and melancholy. There's even a touch of Turner's Fighting Temeraire (painted 30 years previously) in the image of the ships in the distance.

But the most striking thing is how, with its search for the beautiful line, the flattening of form and the sinuous line of the dancing girls, this expressive synthesis by Degas completely prefigures Matisse's La Danse by 40 years. Forty years!!

Henri Matisse, La Danse (Oil on canvas, 1909)

I wanted to take Peasant Girls off the wall and take it back to my studio for ever and ever. Despite the derision of the gallery-going public, for whom it so clearly stood out like an ugly, sore thumb, this, for me, was a painter's painting, and a breathtaking tour-de-force at that.

By the 1880s, Durand-Ruel was able to start buying Impressionist artworks again, thanks to some new financial backing. In order to announce that he was back at the helm, he came up with the ground-breaking idea of holding a series of month-long solo exhibitions. We take such exhibitions for granted now, but this was brand new at the time.

In 1883, Durand-Ruel gave Monet the full works for his show - adverts, images released to the press, and a huge private view - again, all part and parcel of the modern solo show. Despite this, things were strained 5 years later, when Monet and Pissarro started selling well with other dealers. But by 1890, Monet was back asking Durand-Ruel for 20,000 francs to buy his house at Giverny.

Later, in 1892, Monet used this platform of the solo show to promote his 'series' paintings, where he took a single motif of a sinuous line of poplar trees along the bank of a river, and repeated it in different weathers, lights, times of day etc. He was able to display these paintings as a complete set, a cohesive whole, before they were split up as they were sold to clients.

They were therefore useful as a creative goal for Monet - envisaging and curating an exhibition space filled with varients on a single repeated motif - and a useful tool for Durand-Ruel to demonstrate his artist's versatility to clients.

"Look, the poplar paintings also come in pastel colours, or dark colours...

By the 1880s, Durand-Ruel was able to start buying Impressionist artworks again, thanks to some new financial backing. In order to announce that he was back at the helm, he came up with the ground-breaking idea of holding a series of month-long solo exhibitions. We take such exhibitions for granted now, but this was brand new at the time.

In 1883, Durand-Ruel gave Monet the full works for his show - adverts, images released to the press, and a huge private view - again, all part and parcel of the modern solo show. Despite this, things were strained 5 years later, when Monet and Pissarro started selling well with other dealers. But by 1890, Monet was back asking Durand-Ruel for 20,000 francs to buy his house at Giverny.

Later, in 1892, Monet used this platform of the solo show to promote his 'series' paintings, where he took a single motif of a sinuous line of poplar trees along the bank of a river, and repeated it in different weathers, lights, times of day etc. He was able to display these paintings as a complete set, a cohesive whole, before they were split up as they were sold to clients.

They were therefore useful as a creative goal for Monet - envisaging and curating an exhibition space filled with varients on a single repeated motif - and a useful tool for Durand-Ruel to demonstrate his artist's versatility to clients.

"Look, the poplar paintings also come in pastel colours, or dark colours...

Claude Monet, Poplars on the Epte (Oil on canvas, 1891, Tate)

- at dusk, or in the sun

Claude Monet, Poplars in the Sun (Oil on canvas, 1891, National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo)

..in the wind..

Claude Monet, Wind Effect, Sequence of Poplars (Oil on canvas, 1891 Musee d'Orsay)

....with an ornate frame, or a plane frame, or you can have it slightly bigger...." etc etc.

Again, it's a symbiotic relationship. Monet set himself an artistic exercise, and Durand-Ruel capitalised on this, showing his clients how they could choose the pictorial variables based around a constant theme. Plus, having such a strong theme gave Durand-Ruel a strong USP for publicising the show.

Whilst walking round the exhibition, I listened to what people were saying in front of the paintings, and a number were commenting on hos many of the works were from American art galleries. There's a very good reason for this.

After the series of solo shows, there was another banking crisis in 1884, and Durand-Ruel was again forced to think creatively to avoid disaster for himself and the group of Impresionists who depended upon him. His solution was to think big, and make a bold move - this time to expand into fresh, foreign markets.

By 1886, Durand-Ruel had organised a show of 300 paintings in New York, exposing the excitingly fashonable European taste to the newly rich American collectors. The show was a wow. Prices went up. Germany, with its progressive collectors, was also eager for the new art. And so American and European museums and collections began to acquire Impressionist work.

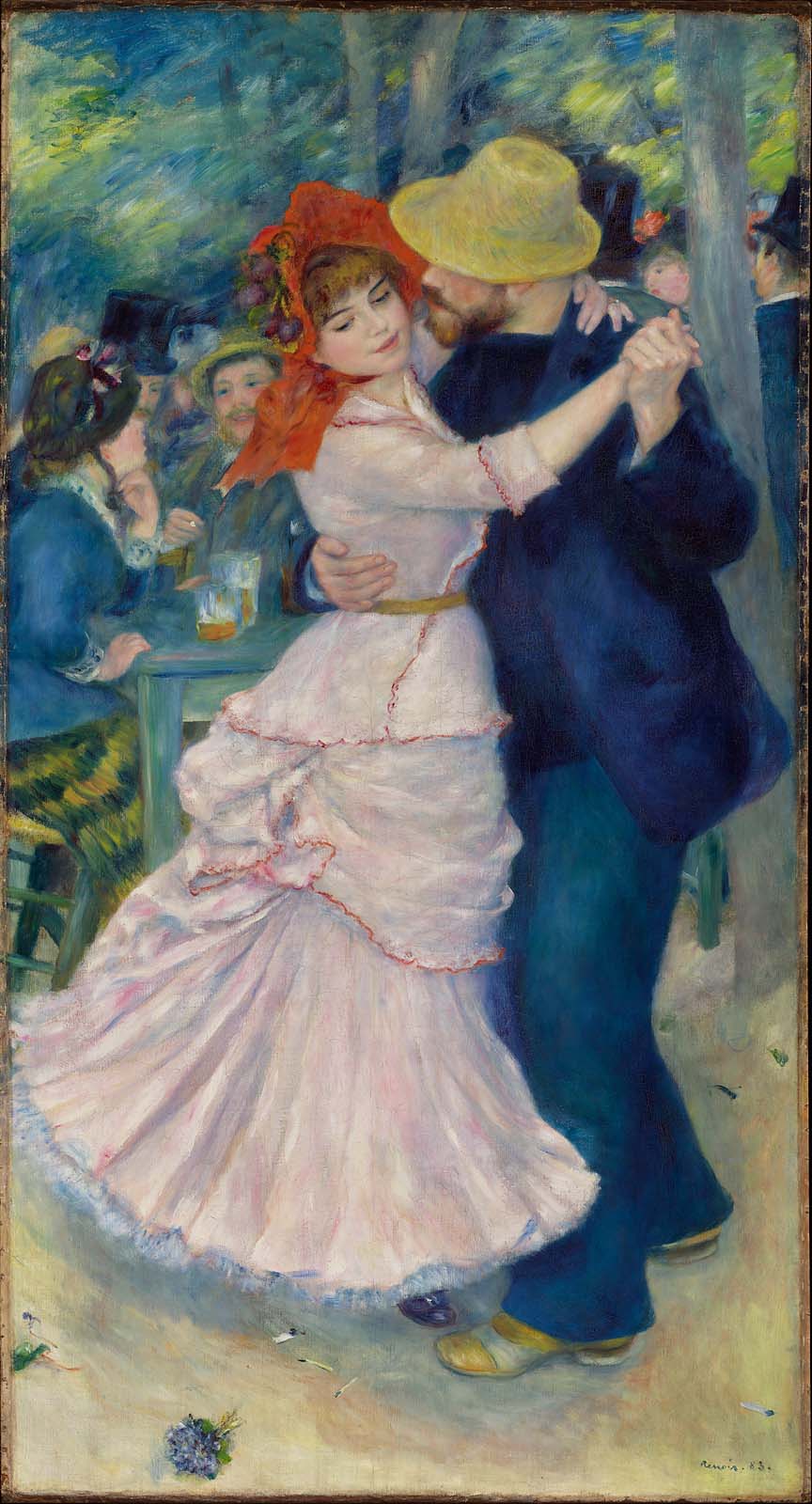

I'm usually not so keen on Renoir, but this was one of my very favourite paintings when I was a teenager, and I had a postcard of it which I loved. It was such a wonderfully carefree, colourful swirl of a painting, very romantic. Who wouldn't want to dance under the trees?

Pierre-August Renoir, Dance at Bougival 1883 (Oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The woman is very much the focus of attention, both the viewers and the man's. This is emphasised by her pretty face being framed by the orangey-red tones of her bonnet, which stand out against all the complimentary blue shades.

However, when you look closer at the real thing, there's an ambiguity in the relationship. There's a palpable tension that she's both enjoying the attention and pulling away. Meanwhile it's the man that is very much driving the action, pulling her towards him.

It's a big painting, and what I noticed when looking at the real thing (which I hadn't noticed before because my postcard cropped off the lower part) was all the detritus on the dance floor - cigarettes, used matchstick ends, a dropped flower posy. Which does make you feel slightly uncomfortable about what's being said in the painting about things being casually used and discarded.

The model for the woman is in fact Maurice Utrillo's mum, Suzanne Valadon. Here she is.

Maybe she was having an off-day.

As far as I can make out, the painting has had around 12 owners, included being consigned to Durand-Ruel three times in 1883, 1886 and 1889. Over the next 50 or so years, it trekked backwards and forwards from New York to Paris, through dealers and private hands, increasing in price, until it was sold in 1937 to the MFA in Boston for $150,000.

So how did it all end?

Well, on to 1905. Impressionism had been around for over 30 years, and new kids on the block such as Picasso were on the scene and painting this sort of thing...

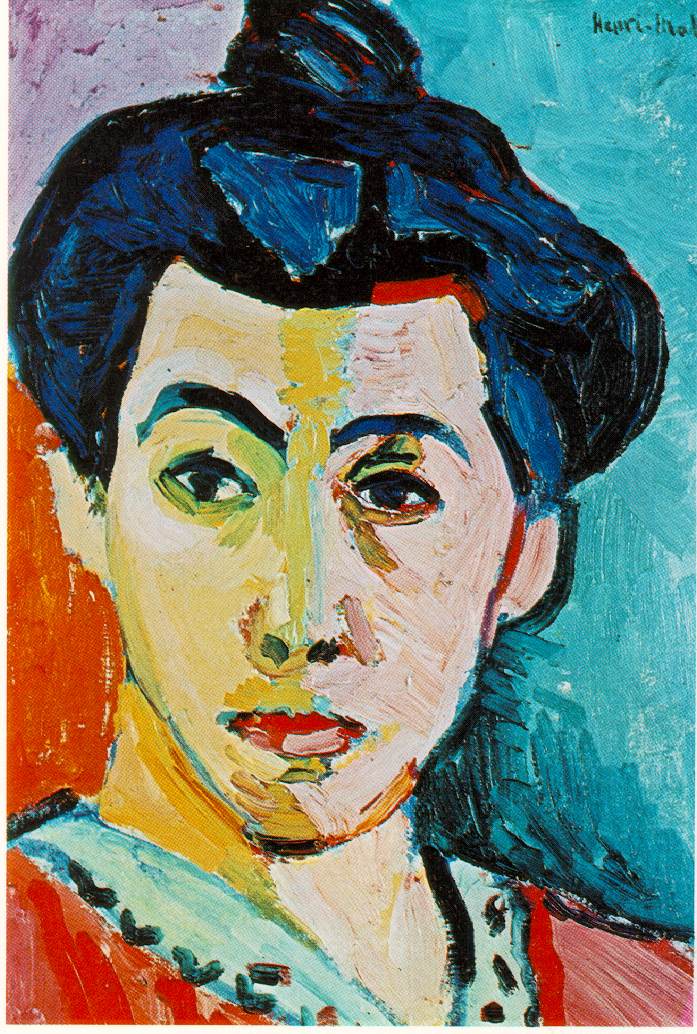

...and Matisse was knocking out this...

As far as I can make out, the painting has had around 12 owners, included being consigned to Durand-Ruel three times in 1883, 1886 and 1889. Over the next 50 or so years, it trekked backwards and forwards from New York to Paris, through dealers and private hands, increasing in price, until it was sold in 1937 to the MFA in Boston for $150,000.

So how did it all end?

Well, on to 1905. Impressionism had been around for over 30 years, and new kids on the block such as Picasso were on the scene and painting this sort of thing...

Pablo Picasso, Two Youths (Oil on canvas 1905)

...and Matisse was knocking out this...

Henri Matisse, Madame Matisse with a Green Stripe (Oil on canvas, 1905)

In other words, Impressionism was accepted as mainstream, and had lost the power to shock, as there were far more shocking things to shock the art world with now. Durand-Ruel therefore felt confident enough to hold the biggest, finest, largest exhibition of Impressionist art ever, at the Grafton Galleries in London, in an attempt to finally crack the British market.

To do this, he curated a show of 315 paintings, including 196 from his own private collection, telling the history of Impressionism. That's an important word, 'curated'. What he was doing in this sweeping panorama of the Impressionist movement was to tell visitors a story. That's what every good art exhibition should do - it should draw you in and take you on a journey, telling you a story. A well-curated exhibition should take you by the hand and lead you through its narrative with its logic.

Included in the show were such weel-kent art history gems as this.

Edouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries Gardens (1862, Oil on canvas, National Gallery, London)

This painting is always a real surprise when I see it, as it's so much smaller than I imagine. It should be huge - all those figures, all those trees! But it's not at all. It's such a strange painting as well.

The title refers to music, and some of the figures are looking out at the viewer. Are we therefore the music, the orchestra? But others aren't paying any attention at all, and the scene is actually quite chaotic. Chairs are facing in every direction. The orderly society is actually very disorderly. In fact, in the section in the middle, you can't actually make out what's happening at all, it's just a jumble of marks. And as for that bendy bendy tree trunk - what's going on? Also, the focus is very strange - some figures in the distance are blurred, others are in clearly identifiable. There are many portraits of Manet's family and friends, and indeed a self-portait as well. Maybe the music is just an excuse to get all these people in the one place.

It's actually a very odd picture indeed.

The public responded well to Durand-Ruel's block-busting extravaganza, and the show attracted huge crowds and critical acclaim.

Unfortunately it only sold 13 paintings, but it had far-reaching influence, and not only laid down the template for gallerists, but created the accepted art historical story of the Impressionist movement. Durand-Ruel had told his own story.

Paul Durand-Ruel retired in 1913. Degas died in 1917, Renoir in 1919, Durand-Ruel himself in 1922 and Monet in 1926. By this time, there had been a world war and the seeds of Modernism were planted. However, Durand-Ruel's legacy is that of creating the modern art market in which this Modernism would be promoted, curated, exhibited and sold.

.jpg/800px-Claude_Monet_-_The_Railway_Bridge_at_Argenteuil_(Philadelphia).jpg)

_by_Matisse.jpg/800px-La_danse_(I)_by_Matisse.jpg)

.JPG/640px-Claude_Monet_-_Poplars_(Wind_effect).JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment